Packing clothes, and deferred dreams

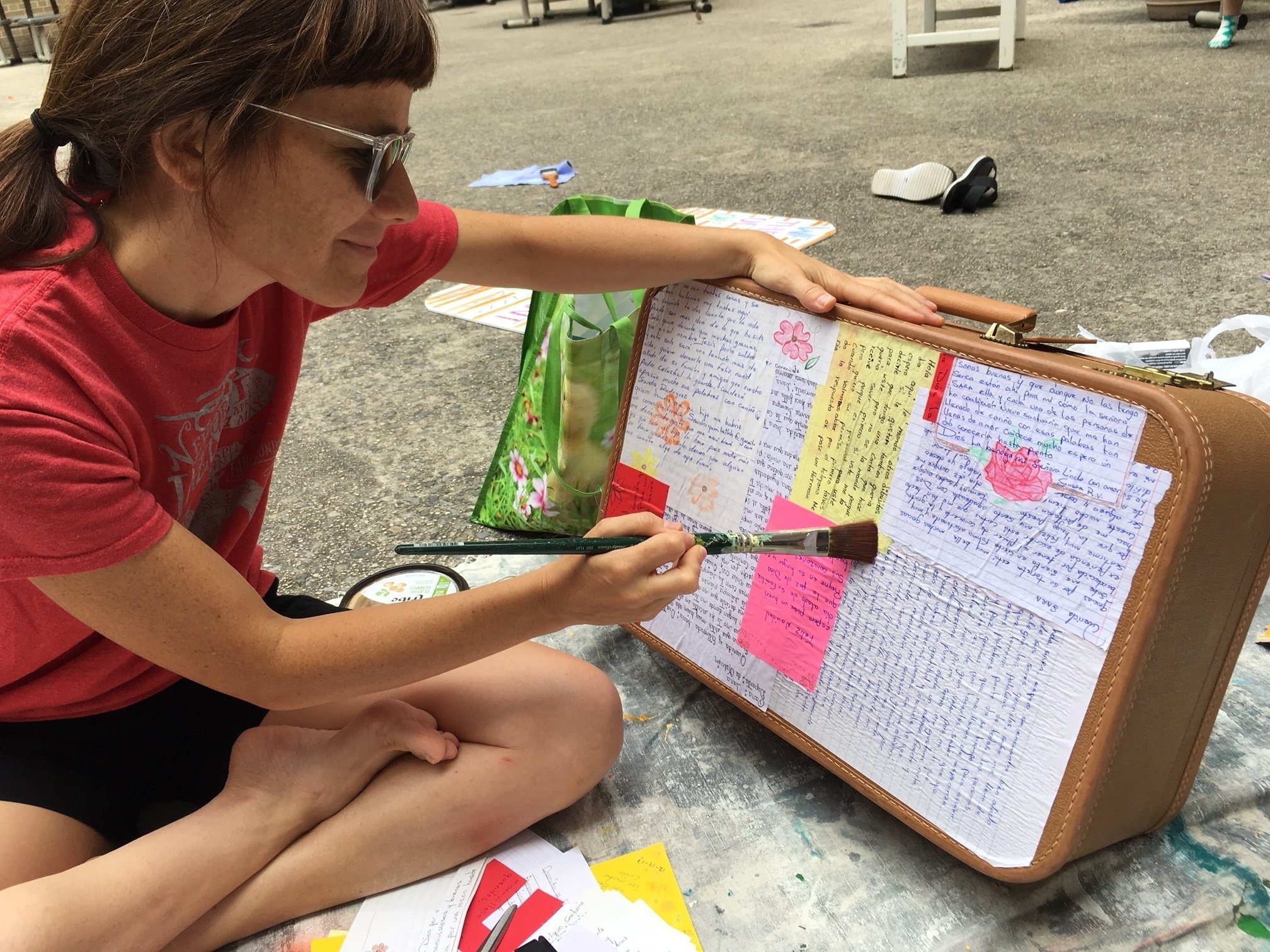

Sara Gozalo, supervising co-coordinator for the city-based New Sanctuary Coalition, decorating the suitcase that she is going to carry to a July 26 march in support of immigrants and would-be deportees. "We have friends who have told us, 'when you are in detention and you get a letter, that's like a treasure,'" she said. Photo courtesy of Sara Gozalo

You can fit a Bible or an extra pair of jeans. You might have to choose between photographs and letters. And do you take the sturdy boots or the formal black shoes?

You think of him stranded on a desert trail, in the scorching heat. But there’s no room for a hat. Or maybe he will be shivering, unable to fall asleep. But a comforter would take up more than half the space.

When U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement orders a person deported, they or their loved ones are allowed to pack one suitcase. It and its contents cannot exceed 25 pounds. Space is limited; possibilities are limitless.

On deportation day, an officer will forage through what you packed, reduce your loved one’s efforts to a compendium of clothing, medications, and those photographs or letters. The memories, though, are yours to keep. Still, you think of all the other things you could have fit.

“Those, by the way, are the lucky ones. Some of them don’t have anyone who can pack a suitcase for them,” said Sara Gozalo, the supervising co-coordinator for New Sanctuary Coalition, a city-based immigrant’s rights organization.

Gozalo is the lead organizer of the Deportee Suitcase Solidarity March, to be held on July 26 at Federal Plaza.

A suitcase, typically a symbol of arrival and of hope, is taking on new meaning for some. Luggage, maybe.

For Thursday’s event, marchers are asked to bring one object they would put in a suitcase should a family member or close friend face deportation.

“The reason why we chose the suitcase is because people don’t think about it. Deportation is becoming a very abstract issue where we talk about numbers, not about each individual family that is being affected,” Gozalo said.

Gozalo, under a program run by New Sanctuary Coalition, has accompanied people dropping off suitcases at ICE headquarters. “It is one of the most painful things to witness, the kind of decisions the person (who packed) has to make. They have to think ‘I only have this much space, what do I put in there?’” she said.

The drop-offs aren’t meant for final goodbyes. There usually isn’t one.

For most deportees, the suitcase and its contents are the only possessions with which they will eventually arrive in a country they haven’t lived in for years or even decades. For many of them, the American dream was also an escape, from poverty, persecution or violence.

On a recent Saturday morning, Gozalo walked SoHo’s streets holding a video camera in one hand, a black duffle bag in the other. Stopping passers-by, she asked, “If you could think of someone you love dearly and that person was about to be deported to a country where you are never going to see them again, what would you pack?”

“But it is totally different ... it is only a thought experiment (rather) than for people for whom it’s a lived experience and who had to make this decision: ‘Can I fit a third pair of jeans in there or not?’” said Carol Scott, also of the New Sanctuary Coalition.

Immigration arrests of people without criminal records have more than tripled in New York since President Donald Trump took office, according to ICE statistics cited by The New York Times.

But Scott and Gozalo argue that the Trump administration is not solely responsible for that increase and also blame the 1996 immigration laws signed by then-President Bill Clinton. “This administration has taken it to a different level, that’s true, but they are only able to do that because of the laws that were created before,” Gozalo said.

The Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act signed into law by Clinton outlined an extended range of criminal convictions — including relatively minor, nonviolent ones — for which even legal permanent residents could be automatically deported.

“Nobody wants to leave their language, country or family until it is a necessity,” said Lourdes Bernard, an artist born in the Dominican Republic and raised in Brooklyn. Bernard is one of the artists collaborating with New Sanctuary Coalition for the Suitcase Solidarity March.

For the march, Bernard will use an antique suitcase dating to the 1930s, another period of mass deportation of Mexicans and Mexican-Americans.

Bernard lined the insides of the suitcase with old newspapers featuring headlines that echo current ones, about war and prejudice, even Russia. “The suitcase is our broken immigration policy. The images highlight why immigrants flee, with U.S. foreign policies acting as a catalyst for war and violence (in their respective countries),” she said.

The suitcase also holds a Dominican flag, which folds out “to invite the viewer to walk around and discover this narrative and history. The movement (the process of folding and unfolding) represents immigrants’ movement and displacement,” Bernard added.

Representatives from the New Sanctuary Coalition accompany about 25 immigrants facing “displacement” every week: to check in with authorities, to court proceedings, to discussions with ICE officials.

Margarita, an immigrant from Ecuador, was one such person. She had packed a suitcase for her husband. The couple had immigrated to the United States about eight years ago. They now have three children. Her husband, arrested for a minor crime, was detained for six months before being deported. “It isn’t just the one person who goes to jail; the whole family lives in this hell having someone incarcerated,” she says on a video recorded by New Sanctuary Coalition.

“When I started to pack a suitcase to bring to his deportation officer, I felt like a part of my life was leaving in that suitcase,” Margarita, who is her 40s and works as a waitress, says. One of her children would cry every night calling for his father.

Margarita packed the suitcase with clothes, shoes, a wallet full of photographs and a Bible.

But, she said, there was room for her to tuck in yet more:

“Broken dreams.”

For the link to the original article: http://www.westsidespirit.com/local-news/20180724/packing-clothes-and-deferred-dreams/1